Much of the developing world is concentrated in subsistence agriculture. However, this does not necessarily mean that all households under such conditions are not productive enough to be otherwise. It is possible that households within a developing country differ in their productivity. The most productive ones could still face poverty simply because they do not have enough land. What is it then that prevents the efficient allocation of land? Does customary law (and the lack of land property rights it entails) play a role?

In BSE Working Paper No. 954, “Land Misallocation and Productivity,” Diego Restuccia and Raül Santaeulàlia-Llopis use state-of-the-art data from Malawi to investigate whether land is misallocated across households and the potential economic effects of efficient reallocation. The authors take advantage of the very detailed data on land usage, quality, input and output of production on the household level, together with a neat but robust economic model to find out that, indeed, land in Malawi is misallocated across agriculture families. They estimate which are the potential gains of efficiently reallocating it and which are the mechanisms that can explain why land in that country is currently not allocated efficiently.

Estimating productivity using micro data

The authors’ work is divided in several steps. First, using the highly detailed data, they estimate the intrinsic productivity at the household level – the total factor productivity – to compare how land is allocated across differently productive families. The authors estimate productivity considering the land quality and potential shocks to the yield with the rainfall at the plot level. They then use a theoretical model to provide a benchmark efficient allocation of land across families given their productivity, and compare that with the actual productivity versus land allocation across families in Malawi.

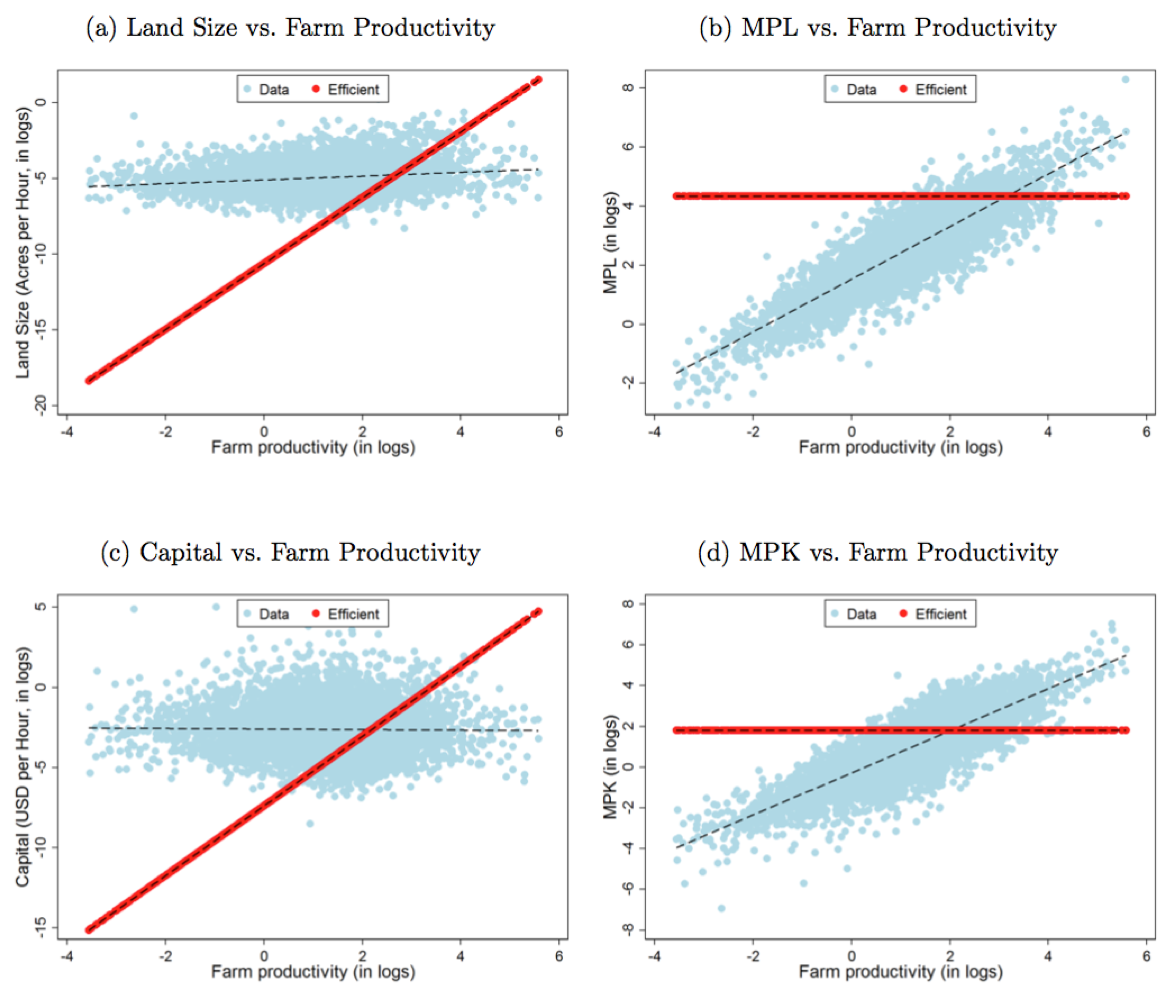

The result, shown in Figure 1, is striking: the actual allocation of land is far different from the theoretical efficient one. In particular, the productivity of the farmer seems to play no role on the farm’s size (panel a). The average land size is almost identical for all levels of household productivity, whereas the theory says that most productive farmer should hold larger plots.

The results appear to be similar for capital allocation. When the authors evaluate the change in total agriculture output if capital is reallocated following the optimal benchmark numbers, they find that aggregate agriculture production would increase by 260%.

This result is quite striking when compared to previous studies in China and India, for instance, which found that reallocating capital in the manufacturing sector would increase aggregate output by a much lower number.

Is customary law a source of inefficiency?

Restuccia and Santaeulàlia-Llopis dig further into the issue of the misallocation of lands to identify potential causes of such inefficient distribution of land in Malawi. They focus on the fact that roughly 85% of total cultivated land is subject to customary law and not acquired through the market. This rudimentary system of property rights on land, managed primarliy by local authorities (i.e., village chiefs), accounts for a great deal of the distortion in the factors of production in Malawian agriculture.

When the authors restrict their analysis to the reallocation of non-marketed lands, they find that output would increase by 315%. On the other hand, farms whose lands were acquired partially or entirely through market operations would have gains no higher than 100%. These gains are significant, but the difference in magnitude stresses that the non-marketed land is the main driver of misallocation in Malawi.

Reallocation policies could reduce income inequality

A final topic approached by the authors is the potential structural changes that such reallocation could impose, in particular on the share of individuals working in agriculture and non-agriculture sectors and income inequality.

Economists consider that poverty in countries like Malawi can be mainly attributed to the importance and inefficiency of their agriculture. That is, the agricultural sector in such countries holds a major share of the population and is, in general, very inefficient, leading to very low levels of income in that sector and, consequently, in the country.

Using a model of structural change, they find that such reallocation policy would bring both agricultural productivity and employment shares close to those of modern, efficient economies.

As a final exercise, the authors show that, under efficient land markets, less productive farmers would be better off renting their lands to the most productive ones, which would lead to optimal reallocation and reduce income inequality in the country.

Conclusions

Restuccia and Santaeulàlia-Llopis perform an extensive study of the gains of land reallocation to find that, in the case of Malawi, the institutional setup of informal land markets accounts for much of the inefficiency in that sector.

Given the remarkable magnitude of the gains estimated in terms of output and income inequality, the authors’ research is inspiring for any policy maker when designing policies for countries of similar context. Their message is clear: allocating the same amount of land for everyone neither leads to efficiency nor reduces income inequality, but allocating the land and letting individuals later trade under efficient land markets does in fact do so.

Image source: Wikipedia