Given the prevalence of posted prices in the Western world, it is easy to forget that they are a relatively recent phenomenon in the history of commerce. The first documented instance in the world occurred in Tokyo in 1673 and the first documented instance in the West occurred in New York in 1823. Since then, posted prices have become the norm for retail goods sold in developed countries.

Under what circumstances does a firm choose to bargain with some consumers in addition to posting a unit price for all others? In BSE Working Paper (No. 1032), “Bargaining at Retail Stores: Evidence from Vienna,” Sandro Shelegia and Joshua Sherman try to tackle this question through theoretical insights and empirical analysis. In the process, they also collect a novel dataset from Vienna to understand the factors affecting the firm’s decision to bargain even when it posts prices.

Posted Prices and Bargaining in Conjunction

Economists have been interested in understanding trading mechanisms in general, and in particular, explaining why and how posted prices have emerged as the dominant mechanism for a retail store to trade. And while posted prices are the norm in retail, there is recent evidence that some retailers do engage in bargaining on posted price, at least for some products. Until now, no formal study has looked at such practices by firms. Through this paper, Shelegia and Sherman fill this gap with a novel hand-collected data set that documents the outcomes of interactions between trained auditors and retail store employees throughout Vienna, Austria. They study a large collection of diverse firms in markets where a majority of transactions take place at the posted price, focusing on how price and firm variation influences the likelihood of a discount being granted.

Study Design

In order to analyze the drivers of a firm’s propensity to bargain, authors hired 12 auditors to visit nearly 300 diverse retail stores in four different commercial areas of Vienna and ask for discounts off of posted prices. The audit study was conducted starting in late 2013 and continued into the first week of 2014, to record observations for pre-Christmas and post-Christmas periods.

Three separate auditors were randomly assigned to each store in the sample using a stratified approach. The auditors were assigned specific stores to visit, find a product in a pre-specified price range, feign credible interest in that product and then ask for a discount. Products surveyed ranged from a posted price of 30 EUR to 999.99 EUR, with a median posted price in the data of 135 EUR.

Data

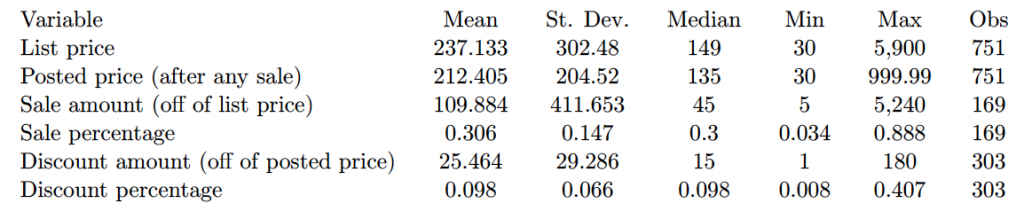

Table 1 below reports summary statistics related to price, sales, and discounts. The posted price is the price that the consumer would pay without explicitly asking for a discount. If the product is on sale, the posted price will be below the list price. Otherwise, the posted price is identical to the list price. The fifth and sixth rows of Table 1 report summary statistics of discounts granted due to bargaining; these cases are conditional on a discount being granted and are calculated off of the posted price (after any sale). In particular, a discount was offered approximately 40% of the time overall, i.e., for 303 of 751 products. This is especially surprising in light of the results of a separate survey of actual consumers conducted by authors in which only 6% of consumers indicated that they asked for discounts at retail stores.

Empirical Findings

Shelegia and Sherman make use of an estimation technique called the lognormal hurdle model to estimate the probability of a discount being granted in the retail store conditional on various factors. The authors find that the probability of a discount increases with the price of the good, implying that a high absolute margin offers more leeway to offer a discount to customers. Secondly, products on sale have a lower probability of being offered at a discount as sale items have lower margins than identically priced goods that are not on sale. Thirdly, a large store or multinational chain is less likely to offer discounts, supporting the notion that per-employee monitoring costs are higher at large-scale firms, a view that is well-supported across the literature dealing with firm size and control-loss. Additionally, authors estimate that the elasticity of discount size with respect to price is approximately unitary and stores which were observed with no customers for a three minute period give substantially larger discounts.

Should we always ask for a discount then?

All in all Shelegia and Sherman undertake the first empirical study of the firm-side factors that influence the retail firm’s trading mechanism. The authors found the very surprising result that many retail firms were willing to supplement their posted prices with a discount, i.e., in approximately 40% of the cases in their study. However, authors are quick to note that many interesting aspects remain unstudied which would allow for a more granular understanding of bargaining practices by firms.