What is the effect of government spending on economic activity? This has been one of the most fundamental policy question debated among macro-economists. Curiously enough, however, economists often offer different answers depending on their beliefs regarding an economy’s fundamental drivers and market frictions. In BSE Working Paper (No. 1040), “Fiscal Multipliers and Foreign Holdings of Public Debt,” Fernando Broner, Daragh Clancy, Alberto Martín and Aitor Erce argue that the answer to this question may lie in who finances the government expenditure.

Introduction

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, traditional monetary policy lost its effectiveness in many countries as nominal interest rates approached zero. This propelled fiscal policy to the center stage of the macroeconomic debate. While many countries initially responded to the crisis with fiscal stimuli, several of them have since implemented strict austerity measures. This has motivated a new wave of empirical research on the effects of fiscal policy, particularly on the size of fiscal multipliers (i.e. the magnitude of the economic response to a given increase in government expenditure or the fiscal deficit). In this paper, Broner et al. argue that there is a natural and largely unexplored connection between fiscal multipliers and the foreign holdings of public debt. The authors demonstrate this connection through a simple theoretical model and back it with extensive evidence and rigorous empirical analysis.

Crowding out: how does it work?

Broner et al. offer a simple and natural intuition for why the size of fiscal multipliers may depend on foreign holdings of public debt. There are various channels through which fiscal expansions, either increases in public spending or reductions in taxes, can raise domestic economic activity. But fiscal expansions can also have crowding-out effects on the domestic private sector because the resources used to acquire public debt can detract from domestic consumption and investment. This implies that the crowding-out effect of fiscal expansions is likely to be stronger when they are financed by selling public debt to domestic (as opposed to foreign) residents.

Foreign holdings of public debt

The analysis conducted by the authors spans 18 OECD countries. For the case, of the United States, data on public debt holdings by foreign residents is collected from the Federal Reserve Economic Databank (FRED). For the case of 17 OECD economies, the authors constructed a novel annual dataset of the allocation of public debt between domestic and foreign holders. This data has been assembled from a variety of sources, including the Balance of Payments (Financial Accounts, International Investment Positions), Monetary Surveys and data provided directly by countries’ Central Banks, Ministries of Finance and Statistical Offices.

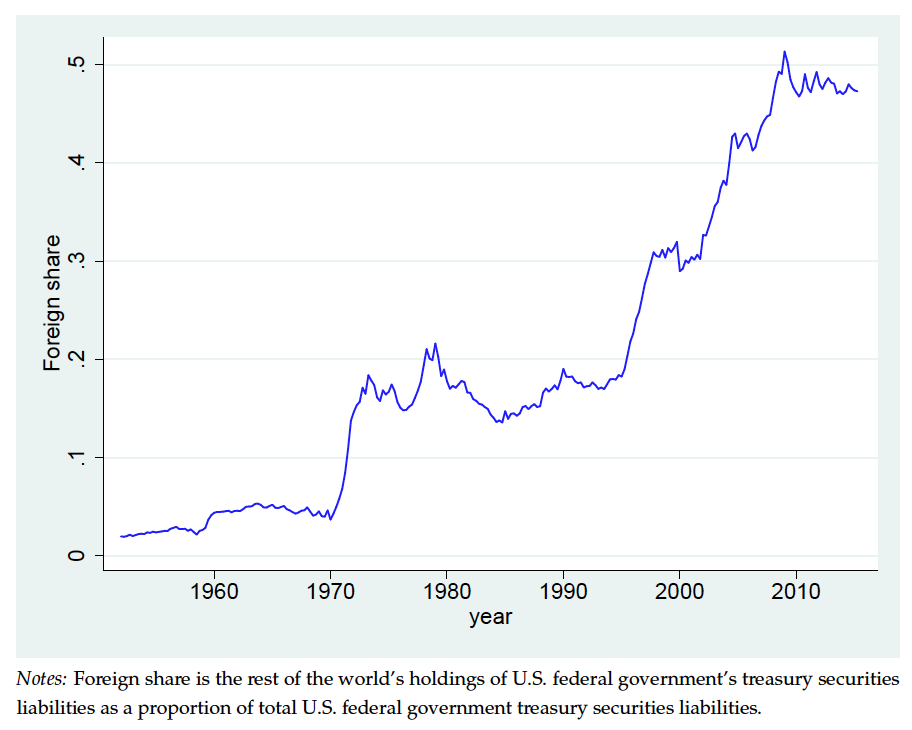

Figure 1 below shows the share of public debt held by foreigners for the United States since the 1950s. The share has increased from less than 5% in the 1950s to close to 50% today. Overall, this trend is not homogenous. In some countries, such as Canada and Japan, the share of public debt held by foreigners is consistently low, whereas in others, such as Finland and Austria, foreigners hold more than 75% of public debt towards the end of the sample. Additionally, during the recent European debt crisis, there was a decline in the share of debt held by foreigners in the euro periphery.

Fiscal multipliers: estimates and results

Consistent with their theory, the authors find that the estimated size of fiscal multipliers is increasing in the share of public debt that is in the hands of foreigners. This result holds both for the United States during the postwar period and for a panel of advanced (OECD) economies over the last few decades.

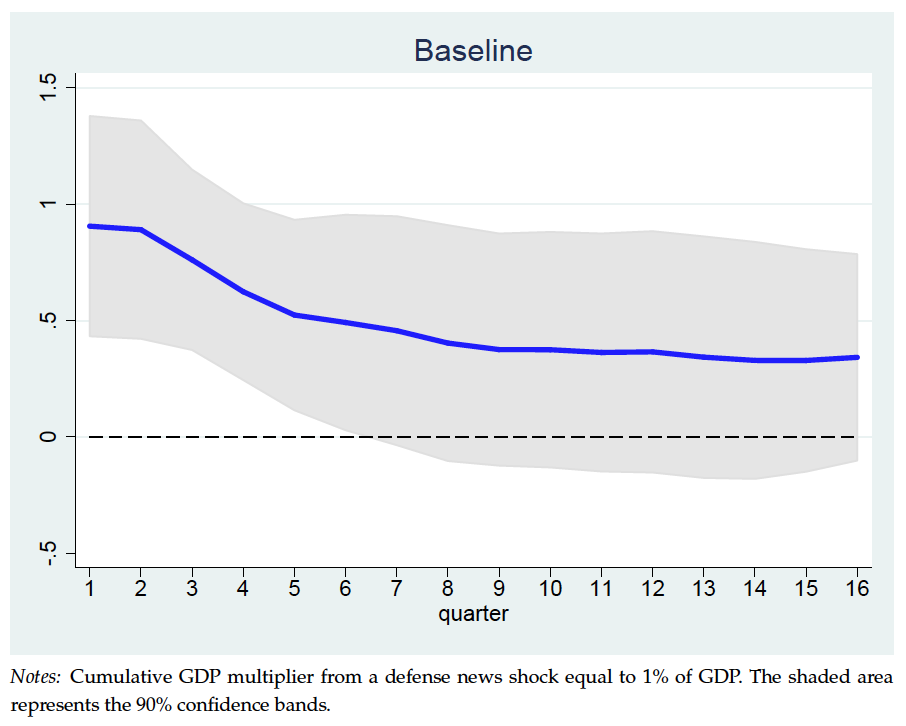

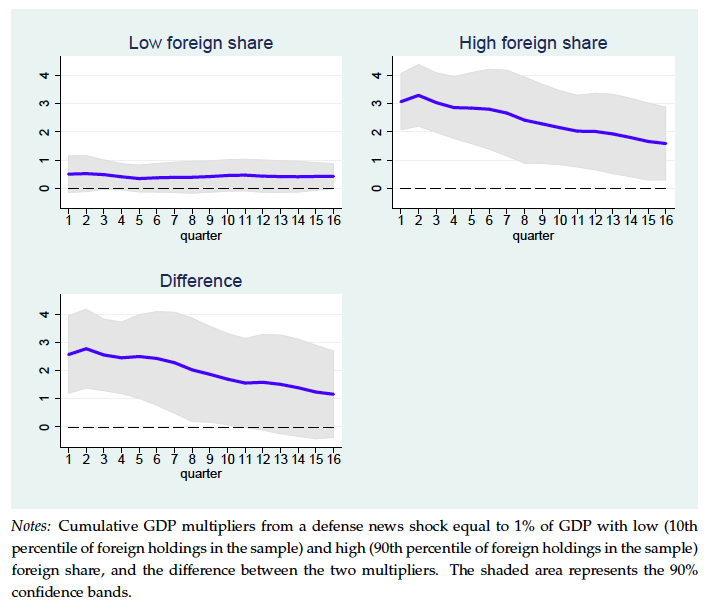

Figure 2 below plots the unconditional cumulative multipliers for up to a four-year horizon for the United States. The estimated multiplier is 0.9 for the first quarter before declining to 0.4 after two years. It is statistically significant at the 1% level for the first four quarters. Figure 3 below plots the cumulative multiplier for up to a four-year horizon conditional on the foreign share of public debt. The first panel in the figure plots the cumulative multipliers for a low foreign share of 3%, which corresponds to the 10th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically indistinguishable from zero and likely smaller than one at all horizons. The second panel plots the cumulative multiplier for a high foreign share of 47%, which corresponds to the 90th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically different from zero at all horizons and significantly greater than one for up to two years. The third panel plots the difference between the cumulative multipliers for high and low foreign share.

Fiscal multipliers: OECD countries

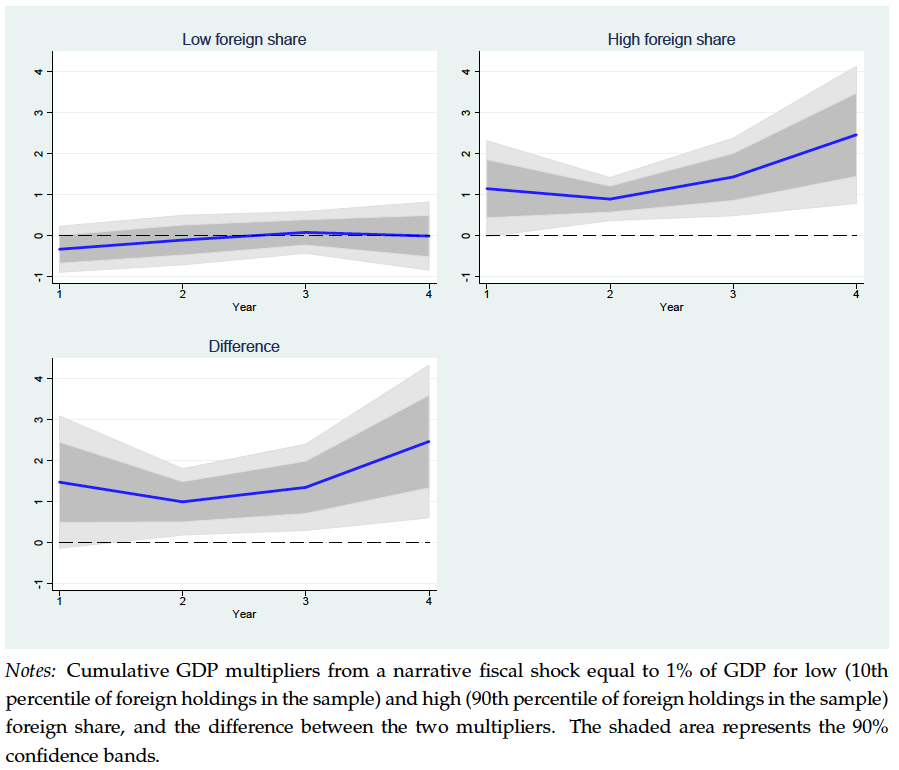

Figure 4 below illustrates the corresponding cumulative multiplier conditional on the foreign share of public debt holdings for 17 OECD countries. The first panel plots the cumulative multipliers for a low foreign share of 6%, which corresponds to the 10th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically indistinguishable from zero and significantly smaller than one at all horizons. The second panel plots the cumulative multiplier for a high foreign share of 66%, which corresponds to the 90th percentile of foreign holdings in the sample. These cumulative multipliers are statistically different from zero at all horizons and the point estimates are above one. The third panel plots the difference between the cumulative multipliers for high and low foreign share. These results are very much consistent with those found for the United States.

Policy implications

All in all, these findings have important implications for the way we think about fiscal policy in open economies. First, they challenge the conventional Mundell-Fleming view by highlighting one channel through which openness raises fiscal multipliers. In a similar vein, they challenge the common perception that, by raising demand for foreign goods, fiscal expansions by one country generate positive spillovers for other countries. Broner et al. instead point to a potentially negative spillover: to the extent that fiscal expansions are financed via foreign borrowing, their crowding-out effects are exported and consumption and investment are reduced elsewhere. More broadly, they suggest that the effects of fiscal expansions in a globalized world depend crucially on how they are financed.