Misconceptions about natural, health, economic and social issues are pervasive in society such as denying climate change and attributing autism to vaccines. Some popular views about how the economy works that are at odds with theoretical and empirical evidence may potentially foster the implementation of policies that have detrimental effects. Dispelling these misconceptions is a challenge because people may stick to previous beliefs even if they are provided with well-grounded scientific information that contradicts them. In the BSE Working Paper (No. 1096) “Dispelling Misconceived Beliefs About Rent Control: Insights from a Field and a Laboratory Experiment”, Jordi Brandts, Isabel Busom, Cristina Lopez-Mayan and Judith Panadés design a field and a laboratory experiment in which they study how to dispel the widespread belief that rent control facilitates access of more people to affordable housing.

The authors test a particular type of intervention –a refutation text– aimed at increasing students’ ability to question their own initial, intuitive beliefs and thus at promoting conceptual change on their wrong belief that rent controls increase the availability of affordable housing. They find that both in the field and in the laboratory a refutation text induces a substantial belief change in the direction of expert knowledge. In the field its impact is significantly larger than that of the natural control, whereas in the laboratory the impact is also larger than that of an appropriate control, but not significantly so. Team discussion on the subject enhances the positive effect of the text for the whole subject pool. However, persuasiveness of the refutation text is higher for less reflective participants when the refutation text is read individually.

Experimental Design

Focusing on the misbeliefs about the rent control, the authors study the effect of a refutational text with two types of experiment: the natural field environment of a college-level Economics degree classroom and a laboratory environment that enables to access a broader population that is not receiving economic instruction. This allows the authors to test the robustness of the effects of refutational text on various subject pools. A refutational text is a specific type of text that emphasizes the negative consequences of the misbelief and refute it explaining the arguments and evidence obtained from scientific research.

Field Experiment

Participants in the field experiment are first-year College students enrolled in a Principles of Economics course at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. Students fill out a survey, which reveals their personal views on rent controls both at the beginning and towards the end of the semester.

The control group consists of students who took Principles of Economics in 2015. The treatment group consists of students enrolled in the same course in 2017. The sample sizes are 272 students in the treatment group, and 340 in the control group. One cohort, the control group, is exposed to the standard lecture and problem session on price controls. In the second cohort, participants are exposed to the refutation text that is discussed in groups.

The authors estimate the impact of the treatment, the refutation text, on the change in beliefs about rent controls regressing the change in beliefs – measured as the difference between a student’s response to the statement at the end of the semester and her response at the beginning – on a dummy variable indicating if the student is in the treatment or control cohort.

Laboratory Experiment

The laboratory experiment is conducted on the non-economics students at the LINEEX (Laboratory for Research in Behavioral and Experimental Economics) of the Universitat de Valencia. In this case, authors look at changes in beliefs at different points in time and with and without group discussion.

The laboratory experiment has three conditions: a control and two treatments. In the control, participants read a non-refutational text that is meant to reproduce as closely as possible the content of the lecture that students are exposed to in the control group of the field experiment. In the first treatment participants read the refutation text individually. In the second treatment participants read and discuss the refutation text in small teams, as in the treatment of the field experiment. As in the field experiment, participants are asked to fill out a survey at different items during the sessions of the laboratory experiment. The sample size is 172 and is equally distributed across conditions.

Results

Focusing on the surveys that the field experiment subjects fill at the beginning of the semester, authors report that initially more than two thirds of students in both cohorts agree that rent controls will make housing available to more families: 69% of the control group and 77% of the treatment.

In the same manner, at the beginning of the session in the laboratory experiment at least 75% of participants believe that rent controls will make housing available to more families: 84% in the control group, 75% in the individual treatment, and 83% in the group treatment.

In the field experiment, at the end of the semester, the percentage of students in the control group in the field holding the misconception is even higher than at the beginning, whereas in the treatment group, there is a response away from the misconception.

In the laboratory, the distribution of beliefs immediately after the intervention shows that the percentages of participants disagreeing with the misbelief increases substantially in all three conditions by a 16-22% change. Three weeks after the intervention, results show a small regression towards the misconception but the percentage disagreeing with it is notably higher than the initial beliefs. Comparing across individual and group conditions the impact of the treatment is stronger for the participants in the group discussion and it does not fade away to the same extent. In the control group, unlike in the field, there is a change away from the misconception.

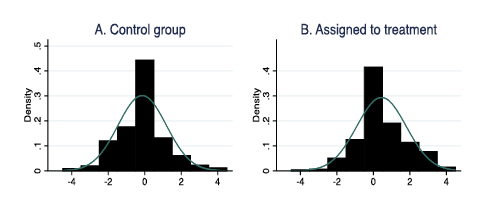

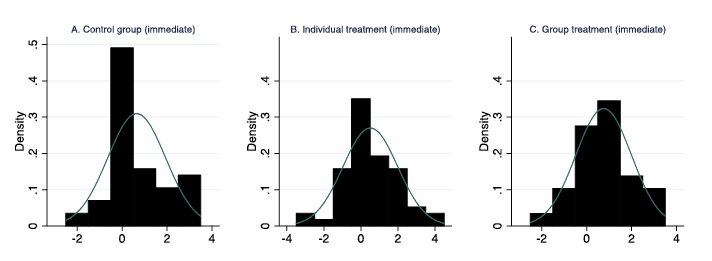

Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of changes in beliefs by treatment condition in the field and in the laboratory. While the distribution for the field control group (shown in plot A of Figure 1) is skewed to the left, meaning that beliefs change in the wrong direction, the distribution for the treatment group (plot B) is skewed to the right. Figure 2 shows similar skewness to the right for both the individual and group treatment, although stronger in the latter.

Results from the regressions on field data also show that estimates of the treatment are statistically significant and positive, which indicates that in the treated group responses are positively correlated with the change from agreeing with the statement towards disagreeing, compared with the control group. In the laboratory, the impact is also positive but not statistically significant.

The authors find that the refutational text intervention reduces the strength of the misconception on rent controls in both subject pools. However, in the laboratory the impact of the refutation text is not significantly larger than that of the control text. They conclude that the refutation text is a good tool for dispelling misconceptions even though other formats can also be effective.