The relationship between compulsory voting, political participation and electoral outcomes has received the attention of many researchers and public figures, and this debate has not yet reached a common conclusion. This debate is even more relevant now, when we see a secular decrease in voter participation in elections around the world, which raises concerns about the representativeness of the results of the democratic process. Understanding the effects of a mandate to vote enforced through an abstention fine is then an important contribution to a better understanding of the incentives to vote and voters’ behavior and to the public policy debate on how to increase electoral participation. In their BSE Working Paper (No. 1111) “How Effective Are Monetary Incentives to Vote? Evidence from a Nationwide Policy”, Mariella Gonzales, Gianmarco Leon-Ciliotta and Luis R. Martinez investigate the causal effect of a fine for electoral abstention on different margins of voter responses in Peru. The authors exploit a nationwide natural experiment emerging from a policy reform that changed the monetary sanction for abstention and affected districts differentially.

The case of Peru

Peru is one of the few countries in the world where a mandate to vote is enforced (along with Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Ecuador, Luxembourg, Nauru, Singapore and Uruguay). The country has more than 20 million voters and enforces compulsory voting since 1933 for citizens between the ages of 18 and 69 (both inclusive). Those who abstain from voting face restricted access to government and financial services until they pay a fine or provide a valid excuse.

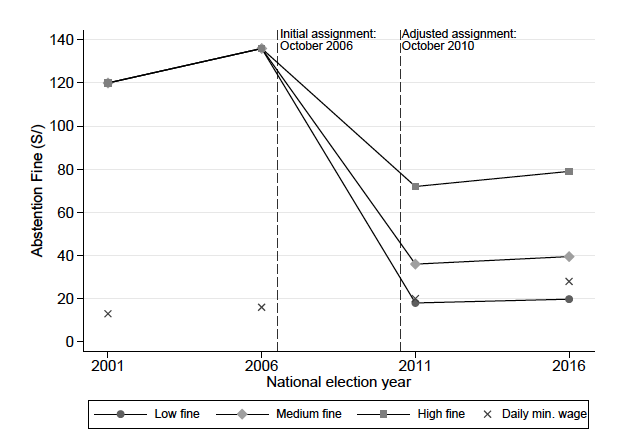

Until 2006, the value of the abstention fine was homogeneous throughout Peru. Districts were divided into three categories (high fine/medium fine/low fine) corresponding to the largest share of their population being non-poor/poor/extreme poor, respectively. Figure 1 shows the value of the fine in each category for the national elections since 2000.

Notes: The graph shows the value of the abstention fine (in current Peruvian soles) in each category for the national elections of 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016, and the nominal value of the legal minimum daily wage for each year. The dashed lines indicate the date of the initial assignment of districts to fine categories (October 27, 2006) and when districts were reclassified (October 1, 2010).

Based on administrative data, the empirical approach is based on a sample corresponding to 94% of the total number of districts in Peru and covering more than 96% of the almost 23 million registered voters in 2016. The data includes the number of registered voters, the number of votes cast and the number of invalid and blank votes in each election by district, as well as the value of the abstention fine by district category.

To vote or not and the value of the fine

The main objective of the paper is to estimate the causal effect of changes to the value of the abstention fine on voters’ behaviour along several margins.

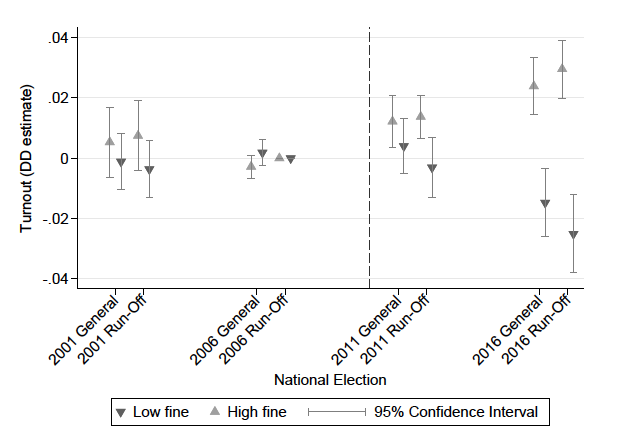

Firstly, using a difference-in-difference strategy, authors show that voters in high fine districts are consistently more likely to vote than those in medium or low fin districts (see Figure 2). On average, a 10 Peruvian Sol [S/] increase (approximately US$3) leads to 0.5 percentage points (pp) higher turnout, with a corresponding elasticity of 0.03 turnout. These results are robust to changes to the specification or to the introduction of additional controls.

Notes: The graph shows point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of a regression of district-level turnout on election dummies interacted with dummies for districts classified in 2010 as “Non-Poor” (high fine) and “Extreme Poor” (low fine). The dashed line indicates October 2010.

Figure 3 below depicts observed voter turnout characterized by a systematically larger turnout during general elections and in high-fine districts. Motivated by this evidence, the authors also investigate the heterogeneous impacts by type of election, time horizon, and poverty. As shown in Figure 2, after the reform, the effect of a same-sized fine increase is more than three times as large in 2016 than in 2011, indicating increased adaptation to the policy incentives over time. In the long run, the differential level of the fine causes a 5 pp turnout gap between high- and low-fine districts. The marginal effect of the fine is also almost 50% larger for the presidential run-off than for the general election taking place only two months earlier, suggesting differences in the marginal voters across election types.

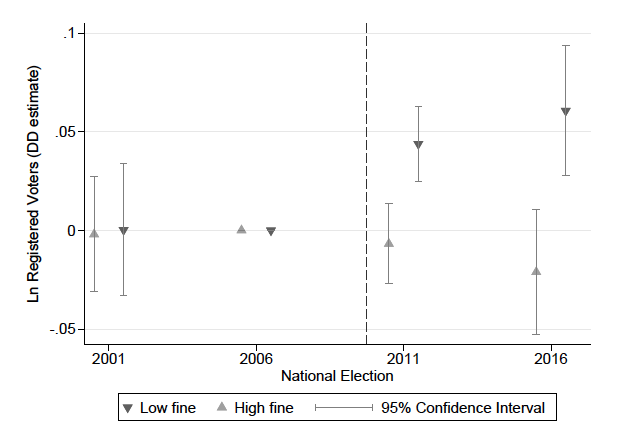

Notes: The graph shows point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of a regression of district-level registered voters on election dummies interacted with dummies for districts classified in 2010 as “Non-Poor” (high fine) and “Extreme Poor” (low fine). The dashed line indicates October 2010.

Finally, the authors also analyse the robustness of the results to changes in enforcement during the sample period. They find that predictors of improved enforcement are all positively correlated with voter turnout in 2016. However, inclusion of additional controls leads to a reduction of no more than 20% in the magnitude of the estimated long-run effect.

Beyond showing up to vote

The authors also investigate the effects of the value of the fine on voter registration, electoral outcomes and benchmark the effects of abstention fines against the aggregate effects of compulsory voting.

In the first aforementioned exploration, they find that the number of registered voters decreases disproportionately in high-fine districts after the reform and estimate a registration elasticity of -0.05. This registration effect is only present for young adults and is mostly driven by first-time voters with ages 18-20, who can strategically manipulate in which district they vote.

As with turnout, the marginal effect of the fine on registration is significantly larger in the longer run. However, the variation in the number of registered voters can explain no more than 20% of the marginal effect of the fine on turnout. Hence, the observed turnout response is mostly driven by people that remain in the same district and adjust their voting behaviour rather than by those with a low propensity to vote self-selecting into low-fine districts. Having a specific group of the population “moving” between districts due to the differential fines can have important effects on representation.

Regarding electoral outcomes, they use the number of invalid and blank votes in each election to represent uninformed or uninterested voters, and investigate if they are affected by the value of the fine. Focusing on the first round of the presidential election, They find that a S/ 10 increase to the value of the fine leads on average to a 0.37 pp increase in the number of blank (0.27 pp) or invalid votes (0.1 pp) as a share of registered voters. This represents 86% of the observed effect of the fine on turnout for this type of election, i.e. for each 10 new voters who decide to participate in the elections due to the fine, 8.6 of them are votes that are not counted towards the final aggregation of preferences. Increasing participation through fines has therefore a very limited effects over final electoral outcomes.

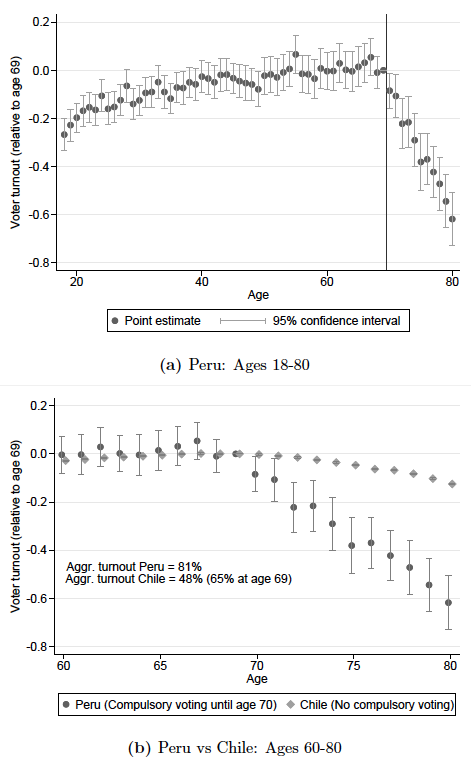

In a second natural experiment provided by the exemption to vote for those above the age 69. Using detailed data on the participation rates of voters by age in each of the country’s voting booths, they find that the senior citizen exemption from compulsory voting leads to a decrease in voter turnout in the range of 20-40 pp, of which the estimate of the fine-elasticity can explain no more than 20% (see Panel (a) of Figure 4 below). Comparing the age distribution of participation with the one in neighbouring Chile, it seems like the vast decline observed at 70 years of age is unlikely to be explained by a natural decrease in participation as voters get older. Authors then conclude the non-monetary incentives provided by compulsory voting vastly out-weigh the monetary incentive provided by the fine.

Notes: Panel(a) shows point estimates of a regression of table-level turnout on the fraction of the electorate registered at that table belonging to each age group from 16 to 122 (estimates for ages below 18 and above 80 not shown). Panel (b) shows the same results for ages 60-80 (round markers). Diamond markers are point estimates of an equivalent regression of individual-level turnout in the 2017 elections in Chile (presidential first round and run-off) on age dummies (estimates below 60 and above 80 not shown). Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Lastly, the authors also explore the relationship between the voters’ information about the modified policy incentives. The result suggests that people are not perfectly informed about the regulatory change and must endogenously increase their demand for information in response to the reform. This endogenous acquisition of information is hypothesized to be one of the main drivers of the increased effect of the policy over time.

Overall, the paper shows that marginal changes to monetary incentives to vote, in the form of reductions to the fine for electoral abstention, have a robust and non-negligible effect on voter turnout. However, the findings also show that voters respond in a rich, multi-dimensional way, indicating that policy-makers must be cautious about the unintended consequences that targeted policies can give rise to.