Photo: Andrea Piacquadio / Pexels

How much would you be willing to pay for a top-notch job position? Do women and men respond differently to such a question? In the BSE Working Paper, “Bidding for the Better Jobs: An Experiment on Gender Differences in Competitiveness without a Real-Effort Task,” Andrej Angelovski, Jordi Brandts and Werner Güth study gender differences in behavior in a competitive environment for better paid jobs in a firm or industry. They introduce a completely new experimental design in which men and women obtain ranked positions in stylized hierarchies by bidding against one other.

Intuitively, the bidding process captures the idea that job competition involves spending resources in a range of ways such as investing in costly training, exhibiting initiative, leadership and working long hours. In this sense, various aspects of how one competes for higher positions in organizations are defined monetarily in the bids.

The experimental study reveals a novel finding: women do not behave less competitively than men. This contributes to the literature by shedding light on the plausible sources of gender imbalances that can guide future research. Such a finding suggests that it is not the conduct of women or the structure of decision-processes per se that lead to gender disparities but instead interpersonal factors, such as the way in which women are perceived and treated by others.

The experiment

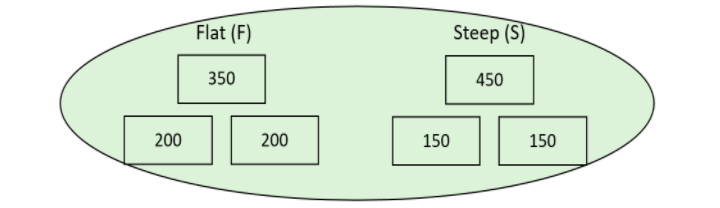

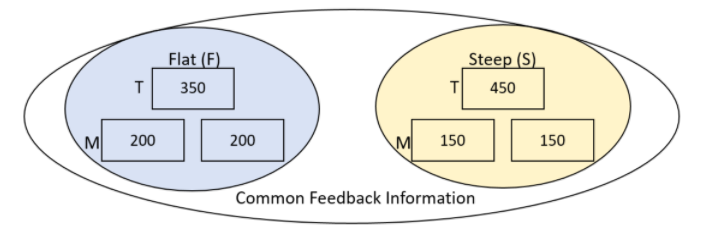

The experiment involves two subsequent phases characterized by intra-firm and inter-firm market competition, in this order. Participants compete for three types of positions: a top one which, if obtained, pays a high prize and two intermediate ones which pay an equal but lower prize. There are two types of firms: one with a relatively flat hierarchy compared to the other, in the sense that the pre-existing payment gap between positions is smaller. For each firm and market, participants have to submit two bids: one for the top and one for the intermediate job posts.

Participants are divided into groups of eight (which does not change during the experiment) and play four times each phase. During intra-firm competition (phase 1), each group is split in two, corresponding to being in a flat or steep hierarchy. Within each sub-group, participants must submit bids for the three positions. Subsequently (phase 2), separate sub-groups are brought together and can bid for any position in both firms, as in broader inter-firm market competition. Hence, each individual files six bids in total: two for the top, and four for the intermediate, potentially better paid positions.

Figure 1 and 2 below depict the experimental environment, where each rectangle is a position and its corresponding prize.

In contrast to previous experimental designs, the setting introduced here quantifies competition among potential workers. Behaving more competitively corresponds to higher bidding for positions. The author’s main focus is whether men and women behave differently with respect to bidding for higher and lower positions.

Results

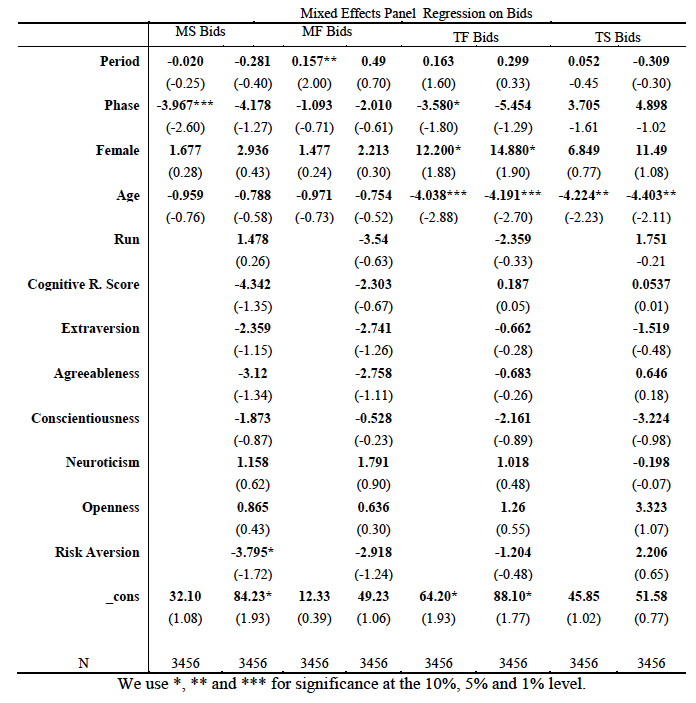

The authors find that women do not behave less competitively. Women bid higher than men, but not significantly so, except for the top position within a firm with a flatter hierarchy. Table 1 shows this result. One can see that gender has a significant effect at the 10% level on bids for the top position only in the flat firm (TF), and that women bid higher than men.

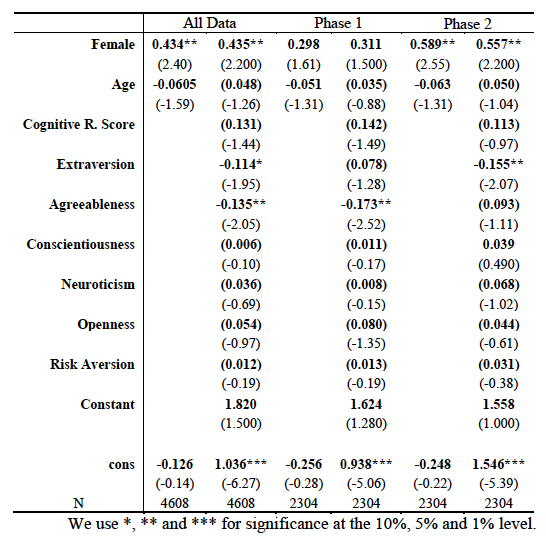

With only this result showing a few gender differences in bidding, it remains unclear if there is gender bias in who ends up getting one of the two top positions. Perhaps surprisingly, women do win the top positions significantly more often. This can be seen in Table 2, which show the results of regressions designed to study access to the top positions in more detail.

These results reveal that there are no significant gender differences in earnings. Furthermore, for the lower prizes average bids approach optimality but are relatively lower for the higher prizes.

Takeaways for future research

Gender differences in competitive behavior have been studied extensively using real-effort tasks and tournament incentives as a representation of competition in society. So far, the results of such experiments suggest that women perform worse under tournament incentives and shy away from entering such competitions.

Unlike in many (but not all) previous experimental studies, this paper shows that women do not behave less competitively. If anything, they bid on average more aggressively, although this effect is very small.

The framework presented here captures key aspects of the job competition process, such as i) in society, as in individual organizations, different positions yield different salaries, ii) to obtain better positions individuals need to invest resources, which depend on the position and iii) positions are allocated through a competitive process.

Nonetheless, the authors point out that this setting is not necessarily a superior representation of competition in society than those of other studies. The important takeaway should be that when studying gender differences with respect to competition, one needs to look at the issue from different angles.