Family benefits, in particular those promoting fertility or targeted to families with young children, account on average for 2.4% of GDP in OECD countries. But the effectiveness of such subsidies has not been empirically corroborated. In BSE Working Paper No. 1153, “How the Introduction and Cancellation of a Child Benefit Affected Births and Abortions”, Libertad González and Sofia Trommlerová provide new insights on this matter. They investigate the case of a universal child benefit for new mothers that was introduced in Spain in 2007 and cancelled in 2010.

By studying the implications of such policy on fertility, the authors show that the benefit led to an immediate increase in birth rates, while its cancellation announcement was followed by a temporary increase and then to a decrease in the number of newborns. They provide novel evidence of the causal relation between the maternity subsidy and fertility, and are able to identify separately the effects driven by conceptions and abortions.

Insights from the behavior of Spanish mothers

The case of Spain constitutes a natural experiment to study the effects of a birth-related subsidy on fertility. The government would “reward” families for each new-born or adopted child, whose birth or adoption date was after the policy announcement. The introduction (July 2007) and subsequent cancellation (May 2010) of the child benefit were both unexpected. During its validity, the subsidy had a nominal value of €2,500, which represented between 150% (when introduced) and 130% (when cancelled) of average gross monthly earnings in Spain. In terms of child raising costs, this amount is estimated to have covered the first 5-6 months after childbirth.

Women may have reacted to the introduction and cancellation of the child benefit with changes in abortions and new conceptions, both of which would lead to changes in the birth rate. The authors point out the empirical importance of distinguishing between these two effects. First of all, conceptions cannot be observed directly. In addition to that, new conceptions happen with a varying time delay after the policy introduction, and also the resulting pregnancies have different lengths (7-9 months). Therefore, it is harder to track new conceptions (and the resulting births) in the data. On the other hand, abortions can react immediately to the policy, and data on abortions are directly available.

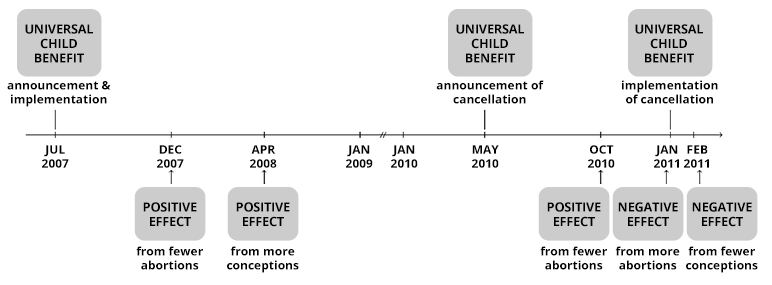

To understand the policy better, Figure 1 presents the timeline of the policy announcements and their potential effects. In sum, González and Trommlerová predict that the benefit introduction would lead to a higher birth rate, while its cancellation would lower it.

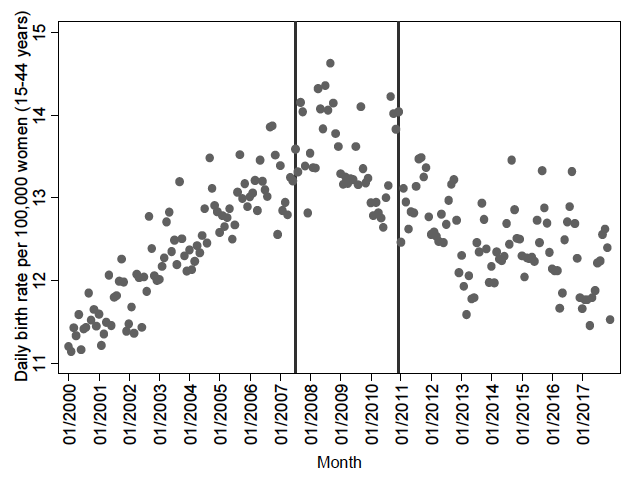

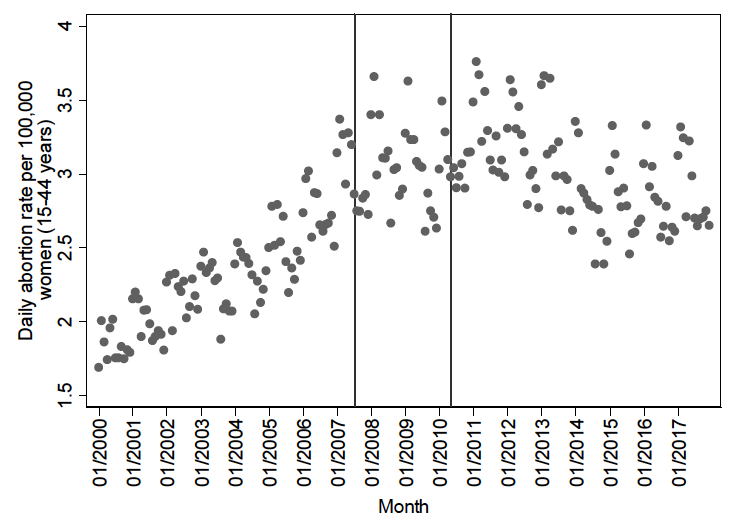

The study is based on population-level data covering all births and abortions in Spain between 2000 and 2017. Figure 2 depicts the birth rate and Figure 3 shows the abortion rate by month in Spain between 2000 and 2017. The vertical lines mark the period when the universal child benefit was in effect. More graphical evidence zooming in on the child benefit period is shown in the working paper, and is in line with the aforementioned potential effects.

Notes: The birth rate is calculated as the number of births per day to women in reproductive age (15-44 years), divided by the number of women in reproductive age, in each calendar month between January 2000 and December 2017, and expressed per 100,000 women in reproductive age. Vertical lines depict the start (July 2007) and the end (December 2010) of the universal child benefit policy.

Notes: The abortion rate is calculated as the number of abortions per day to women in reproductive age (15-44 years), divided by the number of women in reproductive age, in each calendar month between January 2000 and December 2017, and expressed per 100,000 women in reproductive age. Vertical lines depict the announcement of introduction (July 2007) and of cancellation (May 2010) of the universal child benefit policy.

Empirical strategy and findings

To identify the relation between the child subsidy and fertility, authors estimate changes in abortion and birth rates at certain points in time, according to the dates of policy announcements and policy implementation dates.

They find that the introduction of the policy led to a temporary increase in birth rates of 0.9% due to an immediate drop in abortions, and to an additional increase of 1.7% due to a rise in conceptions. Once the cancellation of the policy was announced, there was a temporary increase in birth rates of 4.1% just before the actual cancellation of the policy, driven by fewer abortions, while the longer-term negative effect of child benefit cancellation on birth rates was –5.5%.

In general, the policy effects on fertility were present across all birth orders, maternal age groups, and marital statuses. However, some heterogeneity across subpopulation groups were found. Different occupational groups reacted differently: couples with at least one high-skilled partner reacted to the introduction, while couples with no high-skilled partner reacted to the cancellation of the benefit. Also, economic conditions seemed to be relevant, especially in the reactions to the cancellation: families in poorer regions reacted twice as much, while families in regions more affected by the economic crisis reacted four times as much.

Finally, the findings suggest that the child benefit led to an anticipation of pregnancy for some women (tempo effect), and to an increase in the total number of children per mother for other women (quantum effect). Overall, approximately 70,000 more children were born thanks to the policy in 2007-2010.