Civil wars are interstate conflicts involving large-scale armed combat. Their total death toll in the last 60 years is estimated in the tens of millions. In view of their dramatic consequences, it is not surprising that many have tried to understand the economic and non-economic causes of civil wars. One conclusion has been that downturns in the prices of export commodities increase the risk of civil wars. This has been taken as causal evidence that civil wars are sometimes triggered by economic factors. However, a prominent recent study by Bazzi and Blattman (2014) argues that this conclusion does not withstand reexamination and that commodity prices downturns are unrelated to civil wars. While this contrasts with prior evidence, the new study uses more comprehensive data on commodity prices and exports and can therefore be seen as superseding previous studies.

Antonio Ciccone takes another look at the evidence using the new dataset of Bazzi and Blattman in BSE Working Paper No. 1016, “International Commodity Prices and Civil War Outbreak: New Evidence for Sub-Saharan Africa and Beyond.” He concludes that the new dataset actually confirms that downturns in the prices of export commodities increase the risk of civil war. This is true in Sub-Saharan Africa – the focus of previous studies – but also in a broader sample with countries in the Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia.

The major methodological difference between Ciccone’s analysis and that of Bazzi and Blattman is that Ciccone – following previous work including his own – aggregates individual commodity prices to country-specific price indices using time-invariant (fixed) export shares as commodity weights. Bazzi and Blattman calculate commodity price shocks using time-varying export shares as commodity weights.

Time-varying weights vs. time invariant weights

Countries generally export multiple commodities. To obtain an aggregate commodity price index for a commodity-exporting country, the international prices of its different export commodities must therefore be aggregated somehow. The standard approach is to obtain a country-specific price index as the weighted average of the international prices of the country’s export commodities.

Ciccone argues that the key to correctly estimating the effect of commodity price downturns on the risk of civil war outbreak is to weight commodity prices by time-invariant export shares rather than time-varying export shares. Using time-invariant export shares as commodity weights, ensures that the time variation in the aggregate commodity price shock faced by a country solely reflects (exogenous) international commodity price shocks. Ciccone argues that this is useful as changes in the quantity and type of commodities exported by a country could reflect social, political, or economic changes that affect the risk of civil war in the country. Moreover, the quantity and type of commodities exported by a country may change as a consequence of changes in the likelihood of civil war in the country.

Ciccone contrasts the case where time-invariant export shares are used for aggregation with the case where international commodity prices are aggregated using time-varying export shares. When the export weights used to aggregate international commodity prices vary over time, the time variation in the aggregate commodity price shock faced by a country reflects both changes in (exogenous) international commodity prices as well as (possibly endogenous) changes in the quantity and type of commodities exported by the country. Obtaining country-specific commodity price shocks using time-varying export shares may, therefore, compromise the goal of estimating causal effects of international commodity price shocks.

Data sources

The empirical work of Ciccone is based on the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP)/Peace Research Institute of Oslo (PRIO) Armed Conflict Dataset. UCDP/PRIO defines a civil war as a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/ or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 1,000 battle-related deaths during the calendar year. For the data pertaining to commodity prices and exports, Ciccone uses the data as used by Bazzi and Blattman (2014) which contains shares of 65 commodities in total exports by country and year. The empirical analysis also accounts for rainfall shocks and export demand shocks from OECD countries.

Large effects of commodity price shocks on civil war risk

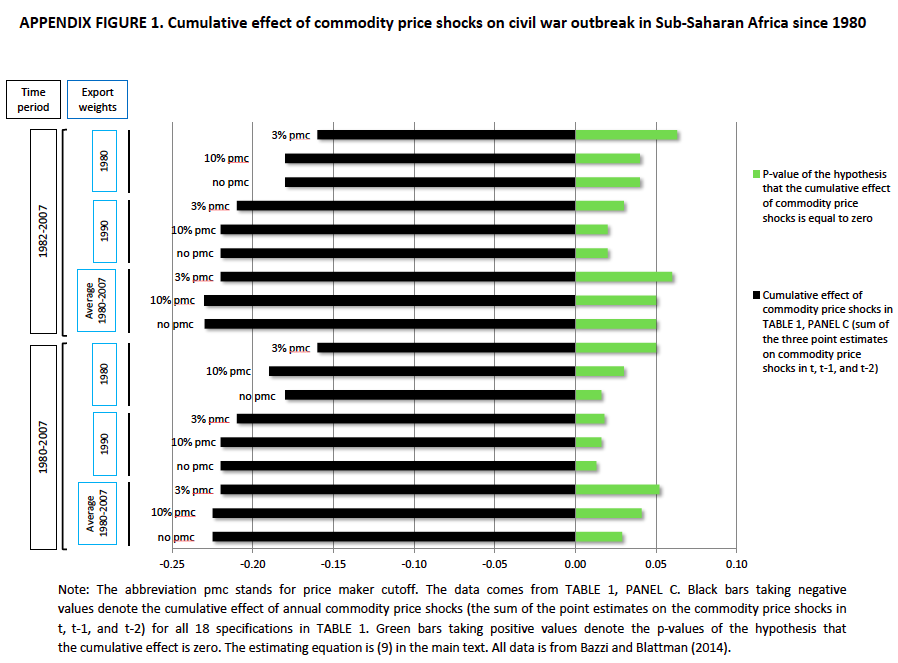

Ciccone consistently finds that commodity price downturns lead to a substantial increase in the risk of civil war. Figure 1 below summarizes his results for Sub-Saharan Africa for the period 1980-2007. It shows the 3-year cumulative effect of commodity price shocks. This effect is calculated as the sum of the effect of a contemporaneous commodity price shock on civil war risk plus the effect of once and twice lagged commodity price shocks.

The figure shows results for the three different ways in which the time-invariant (fixed) commodity export shares are chosen: countries’ export shares in the 1980; in 1990; or the average export shares over the time period examined. The figure also specifies the so-called price maker cutoff (pmc) used. There are again three possibilities: no pmc, 3%, or 10%. A x% pmc implies that commodities are dropped from the price index of a country if the country exports more than x% of world exports. The goal is to make sure that the analysis is not driven by the international prices of some commodities being linked by the conditions in large exporting countries.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the 3-year cumulative effects range from 16% to 22%. These estimates imply that after a sequence of three negative commodity price shocks of one standard deviation each, the risk of civil war outbreak is between 3 and 4 percentage points higher than before. This is a large increase compared to a baseline risk of civil war between 2 and 3 percentage points.

A negative, one-standard-deviation commodity price shock in a single year is found to raise the risk of civil war outbreak in Sub-Saharan Africa by between 40% and 70% of the baseline risk of civil war outbreak.

Similar results hold when Ciccone examines civil war in all large countries in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia. When he differentiates between agricultural commodities on the one hand and minerals, oil, and gas on the other, Ciccone finds a larger increase in the risk of civil war outbreak following downturns in agricultural commodity prices.