This article first appeared on VoxEU.org and features research by Nezih Guner, Yuliya Kulikova and Joan Llull.

Married couples are healthier than singles. This column works to determine the direction of causality by exploiting panel data. In line with the evolutionary psychology literature, healthier individuals seem to be more desirable and are thus more likely to sort into marriage; but there also exists a ‘protective’ health value to marriage. It seems that couples encourage each other to take precautions.

The US economy spent about 18% of its GDP on health care in 2011, up from 5% in 1950 (Fuchs 2013). This dramatic increase led many scholars to look closely at the social and economic determinants of health and highlight their roles in improving population healthcare (House et al. 2008).

One of the key socioeconomic determinants of health is marriage. Married individuals are healthier and live longer than unmarried ones (Waite and Gallagher 2000, Wood et al. 2009, Pijoan-Mas and Rios-Rull 2014). The question is, of course, why? Does the association between marriage and health indicate a causal effect of marriage on health (termed in the literature as the protective effect of marriage), or is it simply an artifact of selection, with healthier people being more likely to get married in the first place?

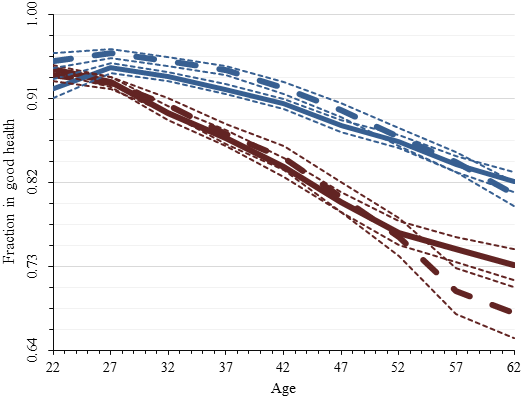

In a recent working paper we try to answer this question (Guner et al. 2014). We study the relationship between health and marriage using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Figure 1 shows differences in health between married (blue lines) and unmarried (red lines) individuals from the PSID (dashed lines) and the MEPS (solid lines) for ages between 20 and 64.1 Age patterns of health and the health gap between married and unmarried individuals are remarkably similar in the two data sets. For all ages considered (20-64), 91% of married individuals indicate that they are healthy, while only 86% of unmarried ones do so. Not surprisingly, at very early ages most individuals are in good health and the marriage health gap is small. At older ages the marriage health gap widens, and among those who are 40 to 64 years old, 88% of married individuals are healthy in contrast to 78% of unmarried ones.

Figure 1. Health and marital status (PSID and MEPS)

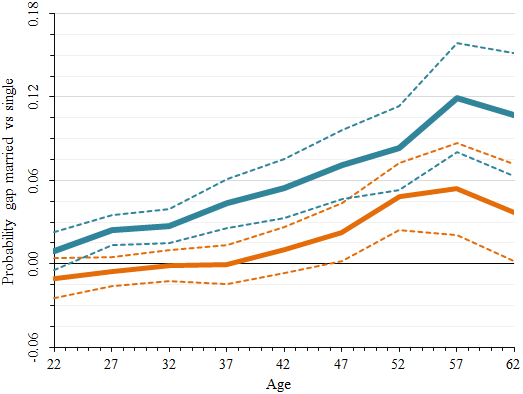

Married individuals could be healthier than single ones due to a host of factors. They usually have more income and are better educated – factors that are known to contribute to better health (Gardner and Oswald 2004, Smith 2007, Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2010). Using data from the PSID, the blue line in Figure 2 shows the marriage health gap after we control for gender, race, education, income, and the presence of children.2 The results show that even after controlling for these observable characteristics, there is a positive and significant difference between the health of married and unmarried individuals. The marriage-health gap is about three percentage points at younger ages (20-39), and increases monotonically to around 12 percentage points for the 55 to 59 age group. The results are similar with the MEPS sample.

Figure 2. Health and marital status: OLS and within-groups estimation results

While the blue line in Figure 2 shows that there exists a positive and significant correlation between marriage and health, this correlation could be generated by self-selection of healthy individuals into marriage. Studies in evolutionary biology suggest that physical and personality traits that define a person as an attractive mate are associated with youth and health, and as a result, with reproductive capacity (Buss 1994, Dawkins 1989). If individuals with better innate health are more attractive marriage partners, they will be more likely to get married in the first place. This would generate a positive correlation between marriage and health even if marriage did not have any positive causal effect on health. We overcome this selection bias by exploiting the panel structure of the PSID.

In the PSID, individuals are observed at many points along their life-cycles. This allows us to clean up the health gap from the effect of a person’s innate health (i.e. it allows us to quantify the health gap between married and unmarried people for a given level of innate health). This is given by the orange line in Figure 2. This line shows the marriage-health gap when individual-specific innate health is also taken into account.3 The size of the marriage health gap is now smaller. Indeed, for ages up to 40 the marriage health gap disappears completely. After age 40, the positive effect of marriage on health starts to show up. At the peak of the gap (between ages 55 and 59), married individuals are about six percentage points more likely to be healthy than unmarried ones. This is about half of the gap in the blue line. These results suggests that there is an important role for self-selection in explaining the observed marriage health gap, especially at earlier ages, while protective effects of marriage on health remain at older ages.

How do selection and protection show up in the data? Consider first selection. Is better innate health associated with a higher chance of getting married? The data show that it is. We show that innate permanent health has a positive and significant effect on entry into marriage – a one standard deviation increase in innate permanent health is associated with a seven percentage point increase in the probability of getting married before age 40. The effect of innate permanent health remains significant when we add further controls, e.g. education, gender, race, and income.

There is also a strong positive assortative mating by health among married individuals. This suggests that healthy individuals look for healthy partners in the marriage market. Table 1 shows that the simple correlation coefficient between the innate permanent health of husbands and wives is about 0.4 (as a comparison, the simple correlation coefficient for years of education among husbands and wives is about 0.5 in the data). When we control for education and race, the correlation remains almost unchanged. Even when we add a measure of permanent income as a further control, innate permanent health is still correlated between husbands and wives (0.33).

[table caption=”Table 1. Marital sorting: Correlation between the innate permanent health of husbands and wives” width=”75%” colwidth=”55%|15%|15%|15%” colalign=”left|center|center|center”]

,(1),(2),(3)

Correlation[attr style=”font-weight:bold;”],0.39,0.38,0.33

Controls[attr colspan=”4″ style=”font-weight:bold;”]

Education and race[attr style=”font-weight:bold;”],No,Yes,Yes

Permanent income[attr style=”font-weight:bold;”],No,No,Yes

[/table]

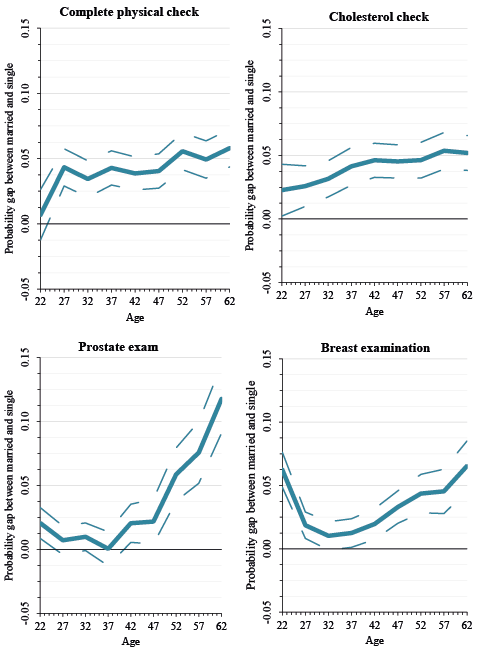

What factors can explain the protective effect of marriage on health? We document that married individuals are much more likely to engage in healthy behavior than unmarried ones. Figure 3 shows differences between married and unmarried individuals in preventive health checks. There are significant differences for all categories of preventive care. Married individuals around ages 50 to 54, for example, are about 6% more likely to check their cholesterol or have a prostate or breast examination. Why would married individuals be more likely to do preventive care? One possible factor, which is well documented in the medical literature, is that having a partner encourages individuals to follow up on their medical appointments, checkups, etc. Another factor is the fact that married individuals are more likely to have health insurance.

Figure 3. Preventive health checks and marital status

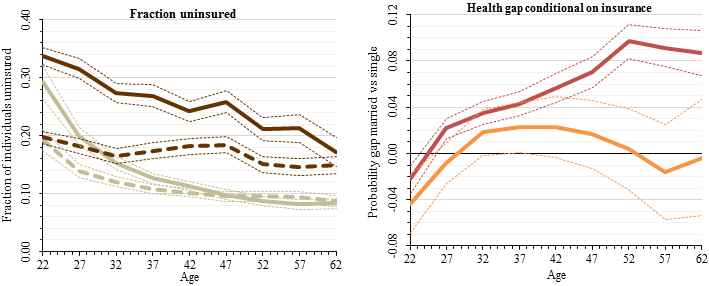

Health insurance status is a key determinant of health care utilization in the US. In the MEPS sample, about 16% of individuals who are between 20 and 64 years old do not have health insurance, any public or private. Panel A in Figure 5 shows how health insurance status differs by marital status for males and females. For both genders, unmarried individuals (dark brown lines) are more likely to be uninsured than married ones. The gap is larger for males (solid lines). The larger gap for males reflects the effect of Medicaid that provides health insurance for children and their parents in low-income families. In the MEPS sample, 9.0% and 17.6% of unmarried males and females have public health insurance, respectively. Panel B in Figure 5 documents how medical insurance affects the marriage health gap. For individuals with health insurance (red line), the results are similar to what we document in Figure 2. Married individuals are healthier and the marriage health gap grows by age. For uninsured individuals (orange line), we do not find any significant marriage health gap. These results suggest that the availability of health insurance is an important facilitator for positive effects of health on marriage.

Figure 4. Health insurance, health, and marital status

Conclusions

We use data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to document differences in health between married and unmarried individuals. Our results suggest that self-selection into marriage drives the observed marriage health gap at younger ages, while at older ages, an important fraction of the observed gap is explained by protective effects of marriage on health. We provide evidence of self-selection patterns in the data, and on different mechanisms through which marriage exerts a beneficial effect on health. We observe strong positive assortative mating in innate health. Innate health is also a good predictor of early entry into marriage. On the other hand, we document that married individuals are much more likely to engage in preventive health care. We interpret these results as indicators of better health production within marriage. We find that health insurance plays an important role in this difference.

References

Cutler, D M and A Lleras-Muney (2010), “Understanding Differences in Health Behaviors by Education,” Journal of Health Economics.

Fuchs, V R (2013), “The Gross Domestic Product and Health Care Spending”, The New England Journal of Medicine.

Gardner, J and A J Oswald (2004), “How is mortality Affected by Money, Marriage, and Stress? ” Journal of Health Economics.

Guner, N, Y Kulikova, and J Llull (2014), “Does Marriage Make You Healthier?” CEPR Discussion Paper 10245.

House, J S, R F Schoeni, G A Kaplan, and H Pollack (2008), “The Health Effects of Social and Economic Policy: The Promise and Challenge for Research and Policy,” in James S. House, Robert F. Schoeni, George A. Kaplan, and Harold Pollack, eds., Making Americans Healthier: Social and Economic Policy as Health Policy, Russell Sage Foundation.

Pijoan-Mas, J and J-V Rios-Rull (2014), “Heterogeneity in Expected Longevities,” Demography.

Waite, L J and M Gallagher (2000), The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier and Better Off Financially, New York: Doubleday.

Wood, R G, S Avellar, and B Goesling (2009), The Effects of Marriage on Health: A Synthesis of Recent Research Evidence, New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Footnotes

- Health is measured as self-rated health. Each respondent is asked to rate their health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. Those with excellent, very good, or good health are considered to be healthy, and others are unhealthy. A similar picture emerges when using objective measures of health or the occurrence of chronic conditions.

- The marriage health gap in Figure 2 is estimated nonparametrically by means of a regression of current health status on the listed controls, a function of age (in our case, a set of five-year age dummies), and the interaction between this function of age and a marriage dummy. The coefficients associated with the latter are the objects plotted in the figure.

- To this end, we expand the model described in footnote 2 by including a time-invariant unobservable term that is potentially correlated with marriage decisions.