Firms are especially vulnerable in their first years of activity. It is practically common knowledge that most bankruptcies occur in the firms’ early years.

External financing is an important ally of firm survival and growth, and can be obtained through traditional sources (e.g., bank loans), but also through private investors. These decide to take part in the enterprise by providing initial funding to later have a share of profits. Venture capitalists and business angels, as they are called in the corporate finance literature, are key players for financing early stage ventures. The reason is that they provide an increasingly popular funding source jointly with a set of (many times unobserved) skills, thus supporting economic growth.

A problem stands on the way of the entrepreneur, though: attracting outside investors is a complicated task, mostly because information (such as financial statements or projections) regarding entrepreneurial firms is scarce, which makes the risk associated with the enterprise difficult to assess. Reducing this “opaqueness” could help new projects to successfully raise funds: reliable financial information on entrepreneurial firms would let private investments flow more easily to those who seek them.

In their BSE Working Paper (No. 941), “Information Asymmetry Reduction in Opaque Contexts: Evidence From Debt and Outside Equity Financing in Early Stage Firms,” Mircea Epure and Martí Guasch investigate how firm debt at early stages is associated with the level of funding obtained from private investors and later performance (as of future revenues or profitability).

In particular, the authors are interested in analyzing whether a firm with higher levels of debt is more or less capable of attracting private funds. On the one hand, high debt could signal a higher bankruptcy probability and therefore private investors would steer away from the firm. On the other hand, however, having successfully obtained debt, would signal that the firm’s characteristics and business projections were analyzed and approved by creditors, reducing the asymmetric information between the firm and potential investors.

Moreover, having debt with specialized creditors such as banks could imply that the firm has a set relation with financial institutions, and thus could potentially benefit from higher buffers through credit lines or longer grace periods, among others. This second line of reasoning can provide a reliable way to reduce the informational asymmetries and risk faced by private investors.

Using data on newly founded companies in the United States from the Kauffman Firm Survey, the authors find that the positive effect prevails, and indeed firms with higher levels of debt—in particular, business debt—successfully obtain more outside equity relative to firms with lower debt levels at their early stages.

The relevance of their study is twofold:

- First, it investigates the potential mechanisms underlying the relation between debt and outside equity—e.g., how debt is used, cash, firm-bank relationship—especially in times of financial distress.

- Second, by looking at representative data on US firms that span eight years after their foundation, their study goes beyond the usual focus on the financial performance of start-ups of a certain age and avoids various potentially misleading conclusions on firm success.

Importantly, the authors address a key issue on start-up behavior by attempting to distinguish between firms that do not seek private funds (e.g., to avoid external interference in managerial decisions) and firms that unsuccessfully seek them. By correcting sample challenges with suitable statistical identification strategies, the authors obtain reliable conclusions.

The main message is clear: start-ups with more debt at early stages manage to obtain more funding from private investors. However, the key insight comes from probing into the different types of debt: it is business debt (as opposed to personal debt) that drives the positive overall relationship with outside equity.

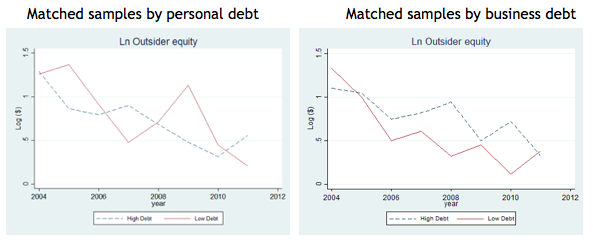

Specialized creditors generally give business debt after assessing the firm and project characteristics, and thus it makes sense for private investors to interpret it as a credible signal. This would not be the case for personal debt. Figure 1 shows—in terms of yearly outside equity injections—that indeed there is not much difference between high/low personal debt start-ups (left figure), whereas start-ups with high business debt receive significantly more outside equity, especially in years of economic distress as 2008 and 2010 (right figure).

In addition, the authors argue that not only the existence of debt reduces the information-related risk investors face, but also its use is of crucial importance.

In particular, new ventures with higher levels of debt have significantly higher levels of cash and inventories in their asset composition compared to lower debt ones. These balance sheet concepts may well be some of the information transmission channels from which investors could benefit when selecting projects.

A complementary mechanism could be the relationship that the firm establishes with financial institutions: proximity to the bank can explain debt levels, and further helps to identify the positive relationship between business debt and outside equity.

In conclusion, Epure and Guasch fill a gap in the entrepreneurial finance literature by identifying the possible mechanisms underneath investors’ assessments of the start-ups’ future potential. Recalling that new firms are an important engine of economic growth, identifying a possible mechanism to enhance firms’ performance is of interest to any policy maker, making this research very relevant also for public policy applications.