Europe has experienced a huge increase in unemployment since the 2008 financial crisis. This rise has been particularly dramatic in southern European economies such as Spain and Italy, which also happen to allow unions to bargain for wages at the sectoral level, an intermediate level of centralization in between firm-level bargaining (as in the United States) and national bargaining (as in Sweden). Could this peculiar union structure be responsible in part for higher unemployment in southern Europe?

In BSE Working Paper (No. 889), “The Calmfors-Driffill Hypothesis with Labour Market Frictions and Regulated Goods Markets,” José Ramón García and Valeri Sorolla show that the bargaining structure of southern European economies can indeed lead to higher unemployment, but that other factors, such as tax progressivity, may play a role as well.

Calmfors and Driffill in their 1988 study proposed that indeed it could, and went further–they hypothesized that all else equal, as the level of centralization in bargaining increases, unemployment would first go up, and then down. This is because economic theory predicts that the amount of clout that unions have when bargaining increases as the unions get bigger and more centralized up to a certain middle point, then begins to decrease as the level of centralization approaches the national level and the bargaining power of the firms, united, catches up.

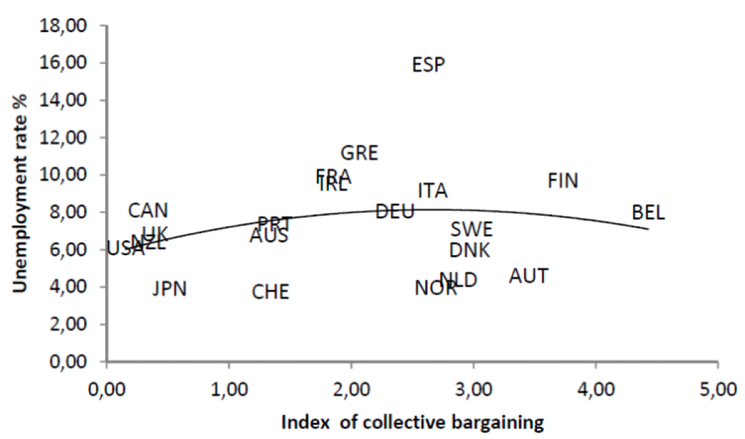

The key caveat of the hypothesis stated above, of course, is “all else equal”–there are so many other factors that go into determining the level of unemployment in a country, that we might expect this “upside-down U-shaped” relationship to be difficult to detect in the data. And indeed, especially after controlling for other factors that might explain the variation in unemployment rates, there is at best only a weak upside-down-U pattern in the data.

Figure 1 plots Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries according to their unemployment rates and an index of collective bargaining constructed by the authors, along with a best-fit parabola. The parabola does show a rising-then-falling pattern, as predicted by the Calmfors-Driffill hypothesis, but this relationship is “weak” and not statistically significant.

Motivated by this puzzling lack of a clear pattern, the authors of the current paper, José Ramón García and Valeri Sorolla, first document a set of confounding factors that may also explain unemployment rates, and then build a model to show that in the presence of these other factors, the expected upside-down-U relationship may indeed disappear.

The authors first gather data on the level of bargaining centralization in OECD countries, placing them in three groups:

- ANGLO, including the US and the UK, with low levels of centralization

- EUCON, including southern Europe, with intermediate levels of centralization, and

- NORDIC, consisting of Finland, Sweden, and other economies with highly centralized collective bargaining.

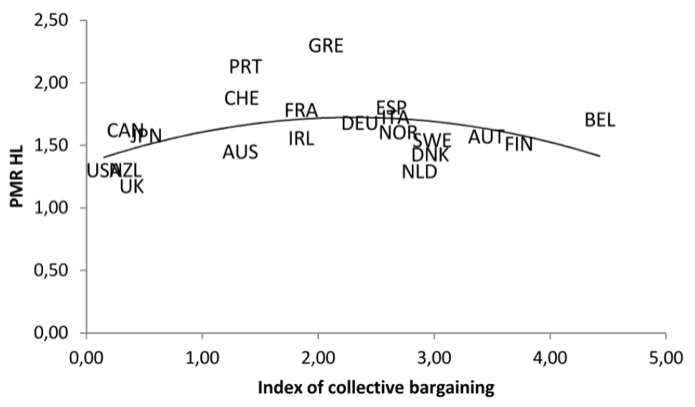

They then compile data on unemployment rates, levels of product market regulation, and the “tax wedge,” or the average percentage of wages that must be paid as taxes. As it turns out, there is a very weak upside-down-U-shaped relationship between bargaining centralization and unemployment; but product market regulation levels also rise and then fall with the centralization of collective bargaining, and the pattern is much stronger than with the unemployment rate.

Figure 2 plots OECD countries according to the same collective bargaining index as before and an index of product market regulation (PMR), with the corresponding best-fit parabola. This time the rising-then-falling pattern is stronger, and statistically significant.

Concluding that the level of regulation as well as other variables might indeed mask any effect of bargaining centralization on the unemployment rate, the authors build an economic model in which wages are higher with sector-level bargaining than with either firm- or national-level bargaining all else equal. This model also accounts for other factors such as taxes and regulations, and shows that if these are not the same in all countries, the pattern for unemployment can break down. Thus they conclude that it is indeed possible for the collective bargaining systems of southern European countries to play a role in their high unemployment rates, though other differences between the south and the north are clearly also important.

Photo credit: Lidia Calderón