Machines have been transforming the labour market since the Industrial Revolution. Concerns about their labour market implications have been raised anew as recent technological advancements have the potential to replace workers in unprecedented numbers. In their BSE Working Paper (No. 1105), “Who is Afraid of Machines?”, Sotiris Blanas, Gino Gancia and Sang Yoon (Tim) Lee study how the widespread use of different machines affected different groups of workers in the recent past.

Same concern, new questions and approach

The improvement of information and communication technologies (ICT), robotics and artificial intelligence and their adoption across multiple industries have often led to the replacement of human workers along parts of the production process. Such is the scale of this phenomenon that many fear that machines may render certain types of workers redundant. If that is the case, it is important to identify which segments of the population have been more vulnerable, and conversely, what kind of worker characteristics have become higher in demand. Understanding the relationship between new technologies and the labour market, and identifying causal channels, is of essence for policy design and implementation.

Motivated by the data and literature, the underlying hypothesis of the paper is that the effects of new technologies on workers may differ by type of capital, such as ICT, software and robots. Moreover, these effects would be heterogeneous across different types of workers as well.

To address these questions, the authors conduct a comprehensive analysis of how various forms of capital such as ICT, software and especially industrial robots, affect the demand for workers of different education, age, and gender across several countries and industries over the last four decades.

To conduct their study, the authors use a unique dataset that comprises 10 high-income countries and 30 industries, which roughly span their entire economies, with annual observations over the period 1982-2005. The empirical investigation consists of exploiting differences in the composition of workers across countries, industries and time.

New evidence-based insights

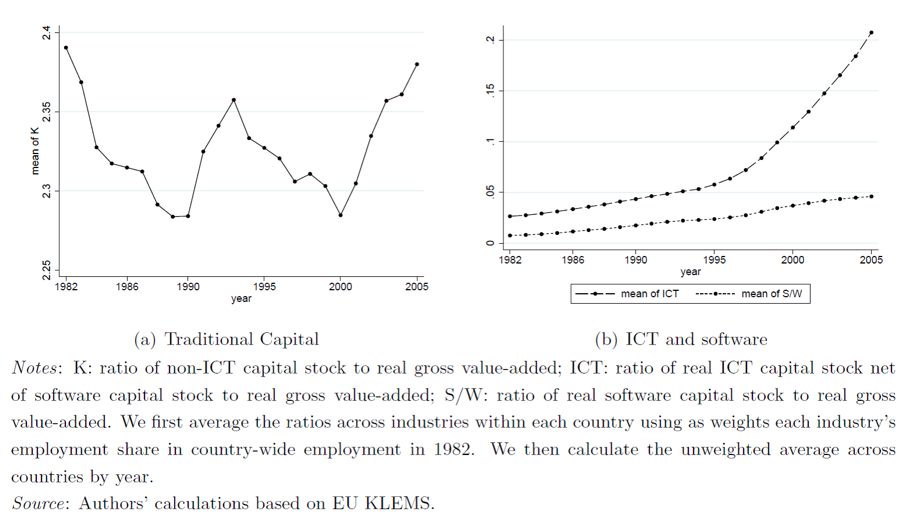

As a preliminary step, the paper reveals some trends in the data. First, there has been a remarkable expansion of ICT and software. Figure 1 depicts the evolution of the capital-to-output ratio by industry for each type of capital, by industry, from 1982 to 2005. While the stocks of ICT and software accounted for less than 3% and 1% of industrial output in 1982, respectively, by 2005 they grew to slightly more than 20% and almost 5%. In contrast, the ratio of non-ICT capital to output does not seem to have evolved in any particular manner.

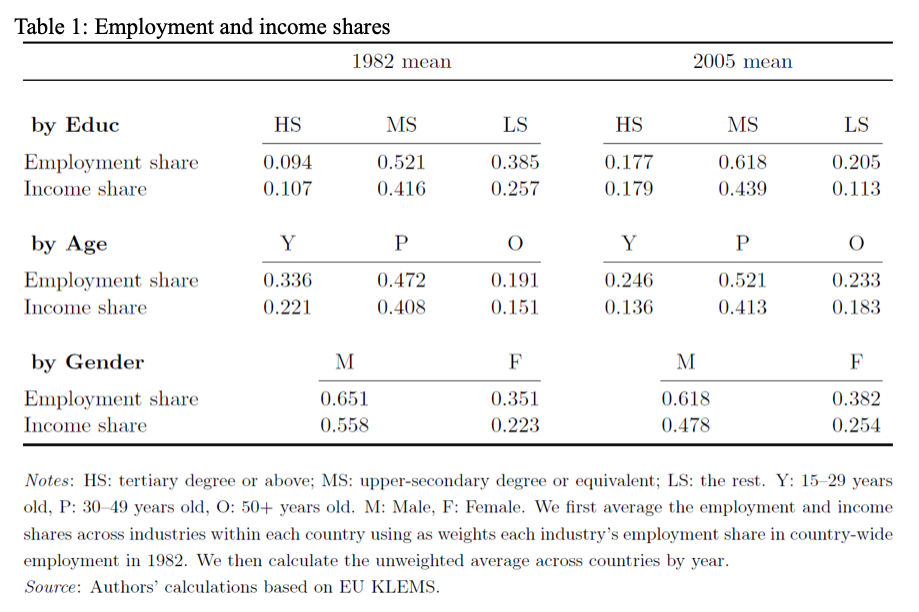

There have also been profound changes in both the employment shares and income shares of different worker types. Table 1 shows employment and income shares by skill, by age and by gender, averaged across all countries in the sample for 1982 and 2005.

High-skill, older and female workers experienced remarkable increases in both their employment levels and income shares between 1982 and 2005. In contrast, there were notable declines in the employment and income shares of low-skill and young workers. Employment shares also grew for medium-skill and male workers, but the changes were relatively small in magnitude, while the income share of the latter in fact declined.

Finally, to explore how new technologies are related to specific tasks the authors investigate how the arrival of new technologies may have affected the supply and demand of each worker group depending on the task content of the occupations they work in. Interestingly, women did and still do work more in occupations that are potentially more easily automated, but over time they have shifted toward occupations that are likely harder to automate.

An econometric approach to rationalize the data

To understand the effects of capital inputs and automation on employment, the authors estimate a labour demand equation in which the dependent variable is the (log-)employment level of each worker type, with non-ICT, ICT and software capital intensities as the main explanatory variables.

The results point to important differences in how labour demand is associated with the three types of capital inputs. Non-ICT capital is associated with employment growth for low-skill and female workers, while ICT is associated with employment growth for all worker types. In contrast, software capital is associated with employment losses for the medium skill, low skill and the young.

Moreover, their findings suggest that the relationship between the different types of capital and labour demand vary by an industry’s exposure to automation. In particular, non-ICT capital is associated with higher employment growth in routine-intensive industries, suggesting that low-tech machines may complement routine tasks. In contrast, both ICT and software are associated with employment losses in more routine-intensive industries, and with employment gains in less routine-intensive industries.

To identify a direct, causal effect of automation, the authors introduce a new variable in the estimation that captures the rise of industrial robots. They find that robots decrease the employment of low-skill workers while they increase the income shares of high and medium-skill workers, old workers, and men. Moreover, the negative employment effects seem to stem mostly from manufacturing industries: In manufacturing, robots lower the employment of low-skill, young and female workers, while in services, they increase the employment of workers of all age groups, medium-skill and male workers. In both sectors, instead, robots increase the income shares of high-skill, old and male workers.

In sum, the paper reveals that software and robots are associated with a decline in employment for low- and medium-skill workers, young workers and women, especially in vulnerable sectors such as manufacturing. On the other hand, these capital inputs are associated with higher employment levels of higher skill workers and men, especially in service industries. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that automation technologies replace humans in routine tasks, in contrast to traditional forms of capital that support them. At the same time, newer technologies seem to complement higher skill tasks: Robots raised the income shares of high-skill, old and male workers, suggesting an increase in the demand for jobs such as engineers, product developers and managers.