Investment in innovation by firms matters. One indispensable reason is that long-term growth in profits depends on it. Yet at the same time, not all firms invest optimally. Several considerations can distort such investment decisions. One consideration that has gained traction in the recent literature is the reports issued by financial analysts.

The literature has identified two distinct effects how analyst coverage might distort a firm’s innovation activity. First, reports by analysts provide reliable information about the firm’s activities and hence reduce the information asymmetry between managers and the public. By reducing the information asymmetries, analyst coverage may increase managers’ incentives to innovate as it decreases both the possibility of market undervaluation of the investments in innovation and the firm’s exposure to hostile takeovers. This is the information effect. Second, analysts typically set short-term earnings goals for the firm, which create pressure on managers because investors react in a negative way by reducing stock prices if the goals are not met. But since investments in innovation do not generally create short-term earnings, the manager in question has incentives to reduce expenses in innovation to meet analysts’ targets. This is the pressure effect.

In the BSE Working Paper (No. 980) “Firms’ Innovation Strategy under the Shadow of Analyst Coverage” by Bing Guo, David Pérez-Castrillo and Anna Toldrà-Simats, the authors contribute to the understanding of the effects of analyst coverage on firms’ innovation strategy and outcome by isolating the information effect from the pressure effect. The authors do so by considering three different channels through which firms can invest in innovation: internal R&D, acquisitions of other innovative firms, and investments in corporate venture capital (CVC) funds, and how each channel is affected differently by the information and pressure effects.

The arguments how the information and pressure effects influence the three innovation channels run as follows. First and related to the information effect, it is more difficult for analysts to understand and report internal R&D activities, which can be quite complex, opaque or even secret, than to value external acquisitions and CVC programs, which typically come with more available information. Hence, the informational role of analysts may be stronger for external innovation activities than for internal R&D.

Second and related to the pressure effect, investments in R&D are expensed in the income statement, whereas acquisitions and CVC investments are normally capitalized. This means that by cutting R&D expenses, pre-tax earnings can immediately be increased and earnings targets for managers are more likely achieved. In contrast, capitalized investments such as acquisitions and CVC programs do not affect earnings in every period. Thus, market pressure by analyst coverage is arguably more likely to distort investments in R&D than in acquisitions and CVC.

Combining the general information and pressure effects by analyst coverage with how they each affect the three investment channels, the authors state the following hypothesis: The information effect (pressure effect, respectively) of analyst coverage, which increases (decreases) incentives to innovate, is smaller (larger) for internal R&D than for external acquisition and CVC. The overall expectation is that analyst coverage has a positive impact on external investments but a negative impact on internal R&D.

The authors then consequently test the hypothesis in an empirical setting by using data of US firms from 1990 to 2012. The number of analysts that cover a firm is used as a measure both for the information and pressure effect. To overcome the potential endogeneity issue in the coverage-innovation relationship, the authors use instrumental variables and difference-in-difference approaches.

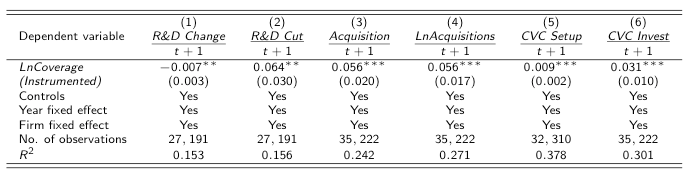

The main results found by the authors are that firms followed by more analysts are more likely to reduce R&D expenses, but to increase investments in external acquisitions and CVC funds, thereby confirming the hypothesis. That is, the results indicate that the pressure effect has a larger impact than the information effect on R&D activities. Conversely, the information effect is stronger than the pressure effect on external innovation channels. The quantitative results for the impact of analysts on R&D, acquisitions, and CVC investments (using the instrumental variables approach) are listed in Table 1 below.

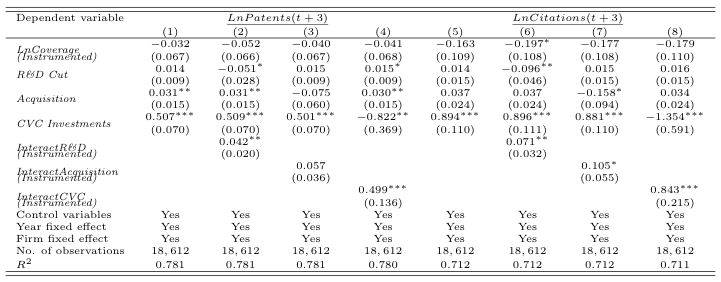

In a next step, given that analyst coverage has both positive and negative effects on firms’ innovation strategy, the authors look at their impact on firms’ innovation outcomes. The authors find that analyst coverage has a negative effect on innovation as measured by the number of patents and citations. But when firms’ investment in internal and external channels is taken into account, this negative effect becomes not significant. In particular, the pressure effect that causes firms to cut R&D can have a positive impact on the future amount of patents. The authors’ interpretation is that the pressure effect, although causing cut-backs in R&D, disciplines managers to cut wasteful resources, which in turn can lead to better innovation outcomes. Lastly, the information effect, which causes firms to invest more in external activities, has a positive impact on a firm’s future number of citations and patents. The innovation outcomes in terms of patents are listed in Table 2.

Overall, the authors find that firms adjust their innovation strategy due to analyst coverage. Firms isolate their productivity in innovation from the harmful pressure effect by analysts, while taking advantage of the information effect.

The paper contributes to the understanding of how analyst coverage affects three main channels that firms use to innovate. One main takeaway is that the results put previous findings in the literature, which highlight the negative effect of financial analysts, into perspective: while the pressure effect indeed reduces R&D activities and hence has a negative impact on innovation propensity, the information effect encourages external investments and thus mitigates the said negative effect.